When Imogen arrives Katharine doesn’t seem to know whether or not to let her in. Imogen hasn’t seen her since school (she hardly spoke to her then). Neither of them can relax until Imogen asks her about the dress.

Katharine: The dress is a copy of two of Ginger Rogers’ dresses, because I loved the skirt of the dress that she wore in Roberta, but I didn’t like the straps. So the straps come from another dress she wore in Swing Time that is far more beautiful, but I believe it cost somebody $5,000 to recreate.

Imogen: How much did yours cost?

Katharine: £500

Imogen: Wow. That’s a lot though, isn’t it?

Katharine: Well, £300 to make, £150 for the silk – and it’s pure silk – and £30 for tax! I wanted it because I go to at least one or two balls a year and I wanted a dress that I could literally wear to every single occasion so I would never have to go and buy another one that I didn’t really like.

The dining room is too full to enter. They make their way up to Katharine’s bedroom.

Imogen: Can I move the lamp behind you?

Katharine: You can move anything you like, seeing as it’s headed for the bin.

Imogen: I don’t want everything to fall off this shelf though.

Katharine: I am quite happy to move everything in here, because, as I say, it’s mostly headed for the bin. When the bulb died in this one, I then couldn’t find another one to fit in it. So actually I could just go and buy a new lamp.

There is a silence.

Imogen: You’re much more comfortable in front of the camera than I am.

Katharine: Well, they say you’re either more comfortable in front of the camera or behind it. I’m the sort of person who can take pictures on holiday; of the view, food or alcohol.

Imogen: I’m just trying to think about your pictures on Facebook and what I’ve seen from those...

Katharine: I hardly put anything on Facebook now. It’s weird; I use my Twitter account far more.

Imogen: Oh really? Well I know you were watching TV last night!

Katharine: Yeah, The Apprentice!

Katharine laughs. Imogen trips on something.

Katharine: It’s only an umbrella and a bag.

Imogen: I don’t want to leave here for you to find I’ve broken something!

Katharine: Don’t worry – the bracelet’s on my wrist.

Imogen: What’s the bracelet?

Katharine shakes her wrist.

Imogen: Oh wow. Was that a present?

Katharine: Yeah.

Imogen: From Ian?

Katharine: I saw it in the duty-free brochure and he was like, ‘Erm, I’ll think about it over the weekend’. I was like, ‘They’re having a sale!’ Although I almost died hearing some of the prices. There was this gold sparkly heart that was really nice and I was like, ‘Ah now I know why it’s so nice’ – it was, like, £182. But hey, I’ve got some nice charms.

They head downstairs to the living room.

Katharine: I should just say: when the desk goes, the record player goes.

Imogen: Where is the record player?

Katharine: In that cupboard. It came from my grandmother’s house, so it’s at least been kept. My records are my treasures because I have lots of lovely records. I’ve got some loooovely 1920’s records.

Imogen: Have you?

Katharine: Everyone’s like, ‘You must have paid a small fortune for them’, but do you know what? There’s not a huge following for Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers. I mean some of them will go for enough, just because.

Imogen: I bet.

Katharine: Eventually I can get my own record player out from where it’s hiding under my bed. Along with the printer.

Imogen: Well you’ve just got to sell some stuff and then you can get them down!

Katharine: I’m trying to persuade my parents to buy my sofa.

Imogen: But then won’t you need a new sofa?

Katharine: No, Ian’s got one.

Imogen: Oh, that’s cool. So when’s he moving in?

Katharine: Well, ’cause he’s flat sharing at the moment and his flatmate’s moving out in July. So he’s kind of like, ‘Well I’ll either need to look for a new flatmate or we can move in together’.

Imogen: Is he messy?

Katharine: Well his bedroom wasn’t the tidiest.

Imogen: Sometimes in a couple you have one that’s really tidy and one that’s really messy. Will he move in and tidy or will he move in and just... like it?

Katharine: No, I’ll just find tidying easier. People are like, ‘I’m not coming round to help you tidy your house’. It’s like, ‘No no! You come round and I’ll tidy and you can sit on the sofa and chat!’

Imogen: That’s true. It’s nice to have company.

Katharine: Plus, with the addition of finishing uni, once I graduate, all my stuff can go in the bin.

James was his friend and was living with us when we broke up.

I hated thinking about how he must have thought of me at that time, when I’d resented him for being a constant reminder of what I’d lost. It wasn’t James’ fault of course; he just had the misfortune of being around before it happened and still there after. Eventually, I asked him to move out.

That’s why I was so surprised when I met him on his lunch break and he seemed so relaxed, so friendly. Unprompted, he began to tell me that he understood how hard it must have been for me and, for the first time, I realised how much he cared about me. Somehow, away from the old flat and its fug of hurt feelings, we seemed able to see each other more clearly.

We had a cup of tea in a café opposite his work and I photographed him outside before I left. He fitted right in to the City.

When Rosie began I was spellbound. I’d looked at her pictures, imagined the photographs I might take, but nothing I’d seen online captured this grace and fluidity. I wasn’t sure I could, either.

I’d somehow managed to convince myself that I needed to repair my relationship with her, but now, watching her move, I realised that had just been the lie I’d told myself to get here. I wanted to see her on the pole.

She had made the underwear she was wearing; pole dancing was just a temporary thing, to help her on the way to becoming a lingerie designer. We didn’t talk about it, but I tried to imagine the men leering over her as she performed. I struggled to see her with eyes other than my own. I knew the seediness of strip clubs, the animal urgency, but I couldn’t believe that it would be that way for her. I didn’t view her performance as sexual, but the thought struck me that perhaps, by photographing her like this, I was using her too.

I saw a rat run across the room behind her. We didn’t talk about that either.

It took me two hours to get ready. I went through outfit after outfit, trying to find a way of incorporating the blue shirt he’d bought me not long after we’d met. I was nervous about photographing him – I feared he might judge the way I worked. I tried to forget that Mehdi was a photographer.

We stayed up late drinking red wine and talking, increasingly comfortable with each other. I tried to tell him how much I liked him, but the words stumbled as they came out.

After we’d had sex, we lay beside each other in a dim lit room. I reached for my camera and moved around the bed, photographing him while he unfolded his body in the glowing light.

Look at the picture, the way her slim arm curves around the small of his back, just the way yours used to. Remember the way your hip slipped so neatly under his? Your bodies always seemed to fit together in every position, like infinitely compatible jigsaw pieces. You wonder if theirs feel the same. She’s taller than you; her head doesn’t fit into his chest like yours did – he said he loved that about you, remember?

She is slim and fit, wearing a baby pink dress that, with her blonde hair, makes her look like a Barbie. You hate pink, but you’re envious that she can wear it. Maybe he likes it now, too.

You can’t deny she looks beautiful in this picture; that bump in her nose has become a flat, perfectly formed little flick. Their smiles match. Look at the way the top of her arm protrudes in a sort of slouchy curve – you hate the way your arms do that too, don’t you? Hers are tanned though, well defined. Maybe yours aren’t so bad either? Your gaze wanders to his face; is he really happy? Might this be a façade? They do look so well suited though. You’re not going to argue with that, are you?

You study the picture further. It has 58 likes. You read your way through the comments and ache and ache and ache.

Tom is my neighbour. He was when we were kids, too. I don’t see him often, but sometimes, in our area, we collide.

I knew he was at the allotment that day because of Instagram. I decided to surprise him.

We went for a walk, shared a smoke, sat on a bench. I photographed him there. He’s a painter. The splatters of bird poo were like brush marks, we agreed.

I didn’t see her as much as I’d wanted when she was pregnant: she’d moved away; things seemed so different. I photographed her on three occasions; we both knew it was the only time we were likely to spend together for a long while.

She was abuzz, bobbing from excitement to tearful anxiety at the prospect of the unknown. She’d fall asleep between shots, waking up to pose like a statue, but before long she’d become uncomfortable and get lost in her own conversation with the baby that was to come.

I told her that her pubic hair was exposed. She said it was only natural: it didn’t matter. When she noticed the stain on her pants she asked me if I could Photoshop it out.

Helen is one of Imogen’s best friends; she’s always the first to tell Imogen she’s her biggest fan whenever she posts a picture online. Imogen tries to keep tabs on what she’s up to. They barely see each other.

While Imogen photographs her – because she is photographing her – Helen tells Imogen about her life now. She is studying midwifery. She puts on her new uniform for Imogen and tells her what she

has learned.

Imogen: OK – we’re recording. What were you saying about your thing?

Helen: (Points at a piece of paper) What do you think any of this means?

Imogen: I don't know?

Helen & Imogen: “Spontaneous vaginal deliveries witnessed.”

Helen: SVB means spontaneous vaginal birth. G3P1 +1 means gravida three – she’s had three pregnancies. Para means how many live children she’s had. So she’s had one live child plus one either miscarriage or abortion. So that’s what that means. And then it tells you about the details of her birth and how the third stage of labour was managed. Do you know what the third stage of labour is?

Imogen: Giving birth?

Helen: No. It’s when the placenta comes out after the birth. And I’ve written how they’ve given birth. The position they were in.

Imogen: When I watch One Born Every Minute I always have to hold my breath when the baby’s born until I hear it cry!

Helen: It’s not just about if they cry. It’s about if their heart is beating and what their colour is like. It’s quite normal for it to take a few minutes. I’ve seen one that needed some help, but I haven’t seen any that needed a lot of help yet. I’m sure I will. I haven’t seen a stillbirth yet.

Imogen fires the shutter.

Imogen: Do you know quite quickly if something goes wrong? And you still have to carry on...

Helen: What do you mean?

Imogen: If the baby dies during labour.

Helen: I haven’t been in that situation yet, so I don’t know... If it’s a confirmed stillbirth they would probably induce normal labour.

Imogen: That’s awful. So you have to go through an entire painful labour?

Helen: Yeah. That’s what my mum had to do.

Imogen: Really? I had no idea.

Helen: Back then, they didn’t show you the baby or anything. They’d just take it away straight away. Whereas today you get asked if you’d like to spend time with the baby and encouraged to have bereavement counselling. She didn’t really see it at all.

Imogen: That’s awful. Do you speak to her about it?

Helen: Yeah, I speak to them about it. I remember when I was younger, asking my dad. I don’t think I knew about it, but I asked him ‘What is the saddest thing that’s ever happened in your life?’ And he said ‘When your mum lost a baby.” I think that’s when I first knew about it. You think your parents are so strong, but it made me realise how awful it must have been to expect a baby and for it not to come. But yeah, my mum does talk about it. I think it’s because she’s a bereavement counsellor.

Imogen: Oh really? I didn’t realise that she’s a bereavement councellor too.

Helen: Well she’s a normal counsellor, but she specialises in bereavement as well.

Imogen: I wonder if that’s why your mum went into it.

I wonder if it’s why you’ve gone into midwifery?

Helen: Yeah, maybe. I have always loved bumps! Especially when my sisters were pregnant.

Imogen: I wonder if that’s why your mum went into it. I wonder if it’s why you’ve gone into midwifery?

Helen: Yeah, maybe. I have always loved bumps! Especially when my sisters were pregnant.

Imogen: I’m not sure I’ve ever felt a baby kick, you know. Actually that might not be true. I’m really hungry.

Helen: Would you like some strawberries?

Imogen: Yes, please, although I should probably go, you know.

I should probably catch the train earlier rather than later.

We had only met the once, when he messaged me to ask if I’d play the role of his lover in a short film. Ruaidhri intrigues me, and I find myself using photography as an excuse to spend more time with him.

One afternoon I ask him if we can recreate a picture of his grandfather that I’ve come across on his Facebook page. That is something he’s always wanted to do, he says.

His grandpa was a handsome man, sat at a kitchen table in Italy in the late 1950s, with light streaming through the plants and onto his breakfast. He hadn’t been permitted to share a bedroom with Ruaidhri’s grandmother at the time. Ruaidhri enjoys the innocent romance of it all.

People commented on the picture, remarked on the resemblance between the two of them.

I see his bedroom for the first time that day. It’s beautifully arranged, almost set-designed, with French novels, oil burners and tin soap dishes dotted around – a careful, curated style I recognise from his blog. I can’t photograph them, he tells me; that is something he wants to do himself. For a moment, we are two artists with hidden, conflicting agendas. I wonder what he wants. If I am not allowed to take photographs of his trinkets, then why am I allowed to turn him into his grandfather?

A few plants and a fortunate shower of sunlight transform his living room, and the shoot begins. But Ruaidhri is tired, hungover, and I am taking too long perfecting the shot. I know when it is my time to leave. I had hoped to be with him longer.

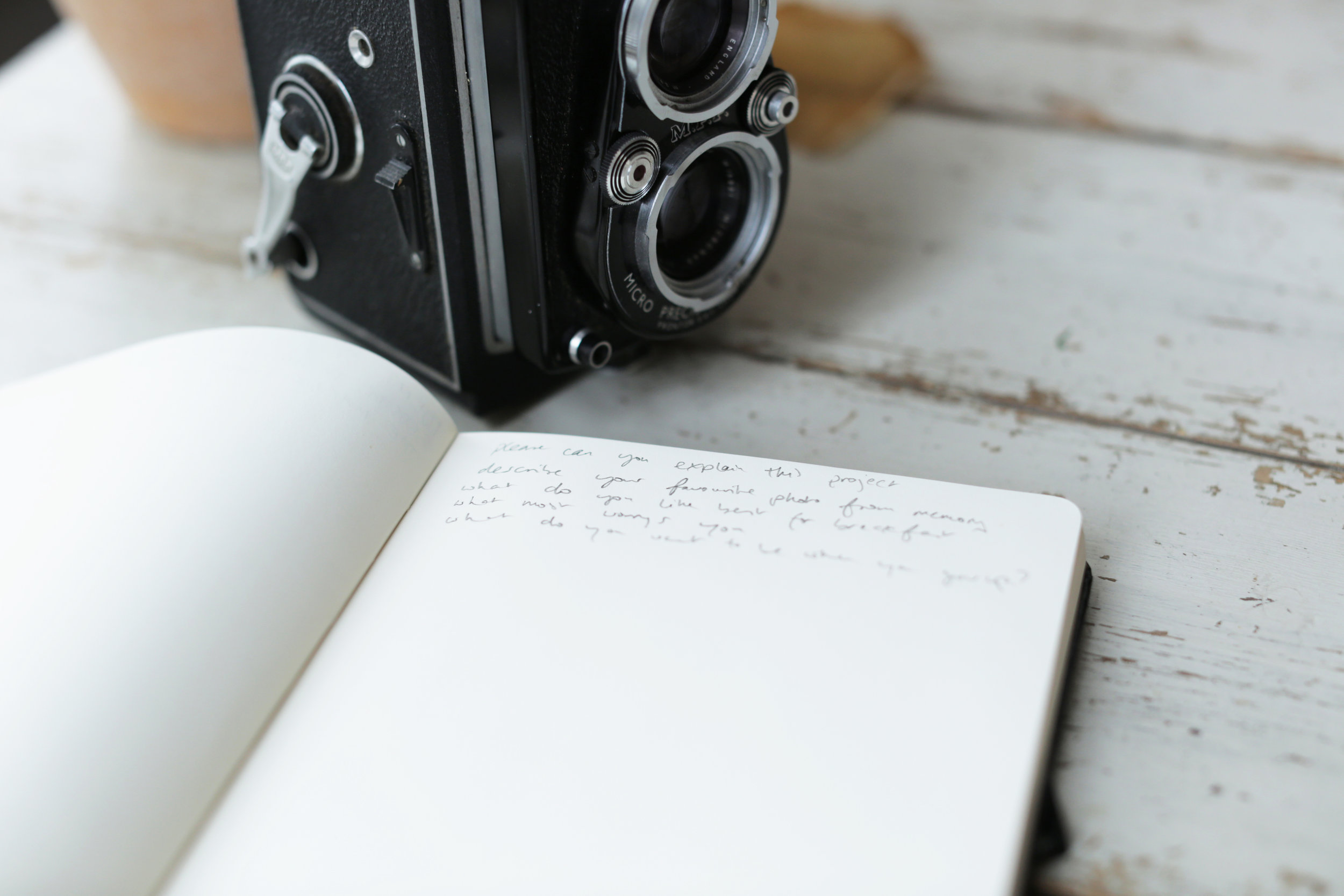

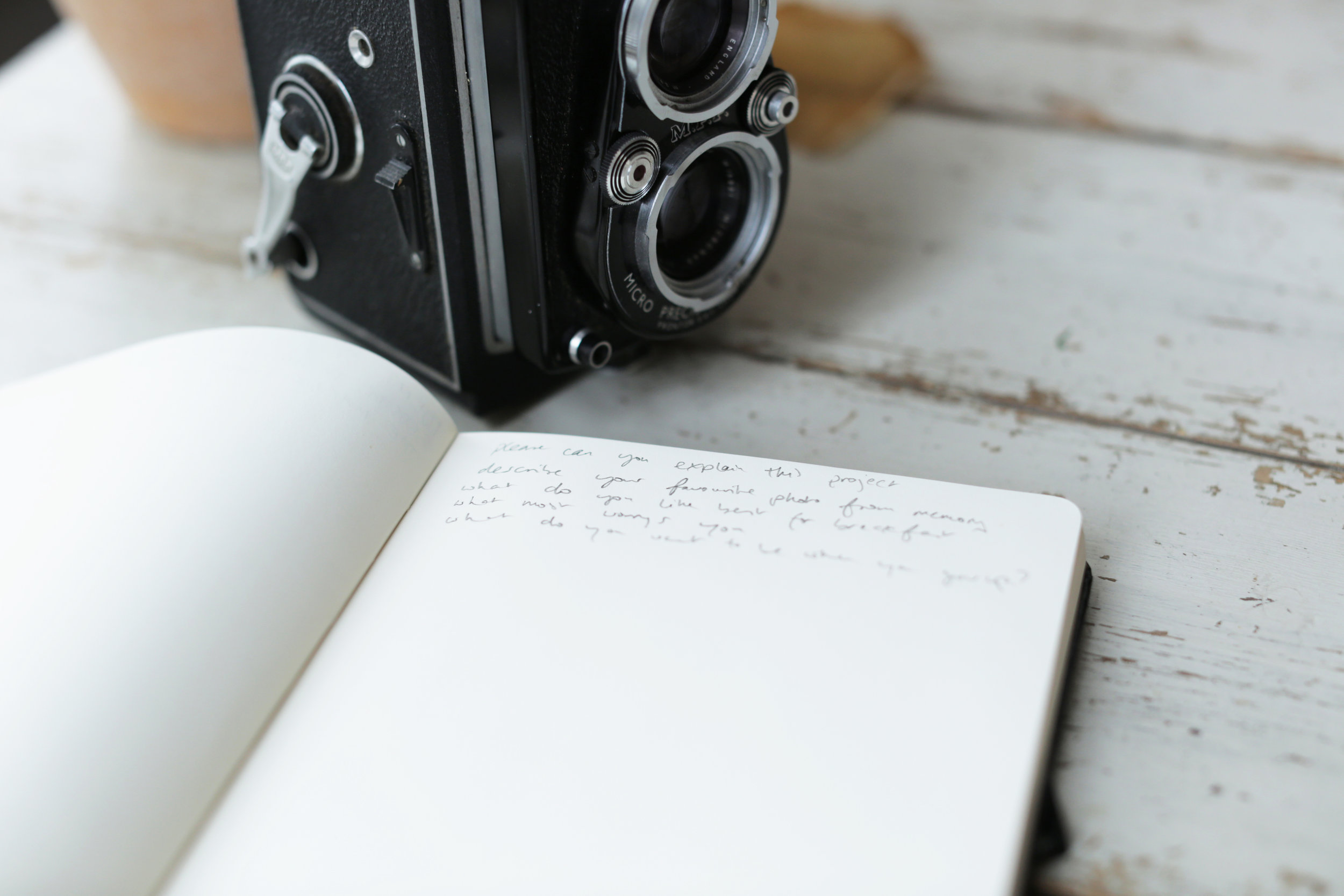

For our second meeting, I’ve asked Ruaidhri to photograph me, but when the day comes I try to postpone it. He tells me he won’t let me put my work on hold any further and that he has prepared some questions he’d like to ask me.

I set up a camera to record us and sit there, tense and unready. He opens a box of panettone, places it on the table, and invites me to eat. He has prepared a playlist for the day. He puts it on and asks his first question:

"What is your project about?"

I am thrown into panic. I don’t know anymore.

Ruaidhri jumps up and escorts me from the room – my room– to the top of the basement steps, where he photographs me.

I wanted to photograph him too, but my camera is in the next room, recording emptiness. I’ve planned for some sort of conceptual cold war, and he’s disarmed me with a playlist and a panettone.

“Describe your favourite photo from memory."

At this moment, I don’t have one. Nothing and no one comes to mind. I tell him I can’t answer questions like this under pressure.He drags me into another room to ‘think’ about my answer and takes more photographs.

In my conservatory, I light a cigarette.

In the end, I describe a picture of my mum that my dad took in the 70s. I don’t think Ruaidhri’s especially interested in that; I think he’s interested in the fact he’s put me on edge.

I smoke while he takes pictures. I think of one of the women I saw in a picture on his blog – a 60s model smoking – an image I knew he liked. I pout my lips and exhale through a heavy fringe. I don’t want to disappoint him.

The third time, I ask Ruaidhri if he will let me take his portrait during one of his own film shoots. He introduces me to the cameraman via email.

We will also be joined by my friend Imogen who will be taking some production photos. She may well shoot some additional wides of the three of us.

It is very quiet when I get there – focused and disconcerting. Ruaidhri has two cameramen working for him. I already know one of them, but my arrival doesn’t seem to trigger much of a response. Benignly ignored,

I get out my camera and take silent photographs of them filming a still life.

It isn’t until halfway through the day, when I have relaxed into things, that I realise that the sounds of our voices, my camera shutter and our movements are being recorded. It suddenly strikes me that my presence plays a part in Ruaidhri’s work as much as his does in mine. I wonder whose project it is today.

I soon find myself taking production shots and forget why it is I am here.

Miss had sent a student to fetch me from reception. I was convinced she planned on embarrassing me somehow, on throwing me into a sea of teenage faces, watching me drown. As I entered the classroom, she waved, tossed over a smile and carried on teaching. I sat on a chair, faced the class and learned about the amount of protein in cheese.

When the break bell rang and I started taking pictures, she asked

her students to join her but they ran away from my camera. She was sad about that – I thought perhaps they acted as some sort of collective comfort blanket. She would help define the people they would become – in return do they define who she is now? That dreaming sea of faces that rolls in and out every year, different but the same?

Before I left, she introduced me to the next class. I felt important, not embarrassed. She hugged me. It was a nice hug, and I felt sorry to say goodbye. I hadn’t the last time.

While I spent the afternoon photographing Helen, Basil was working in the garage at the back of the house. I popped outside to see him and took his portrait while Helen made us some tea. I asked him about motorbike parts.

When Helen joined us, she didn’t seem to understand much of it either. We weren’t out there very long.

Christina is a yoga teacher. I’d see her on Tuesdays, in class. She posts pictures of herself stretching online. I was always blown away when

I looked at them – she’s astonishingly flexible. She told me that, when she was a child, she trained to be an Olympic gymnast. Her mother stopped her – the training was too much, apparently, but it obviously stayed with her.

I’d been to Christina’s house once before I photographed her, with friends for dinner, but never into her bedroom. She told me she never usually presents herself in such explicit positions online. She was worried about being too provocative, I think.

Before we met in person, he called me ‘sister’. We do have a connection: he is an activist and the main subject of a documentary my brother made about the killings of people with albinism in Tanzania.

When I meet him for the first time in Amsterdam, I am already overwhelmed. Josephat is used to having his picture taken by now, although he doesn’t seem to understand why I want to take it. He’s partially blind, and I don’t know if he can see me when I ask him to look at me. I only take a few shots.

He tells me I must use my photography to make great change in the world. I think about it.

I can’t stop thinking about it.

Bea had become a dancer; I hadn’t. Hearing her voice again threw me. It was familiar and different, like déjà vu. She’d retired from performing, she told me, but said that she’d still like to put on her leotard and show me some poses.

She stretched in her hallway, complaining about old injuries. You miss this, I thought.

At one point, she fixed her eyes on me through the lens, asking me, theatrically, ‘What’s my story?’

I said:

‘Your dog’s just been run over.’

She looked at me harder.

I wonder where Joe goes. He seems such an intermittent part of

my life: brief, intense flurries of connection, and the rest is silence. He disappeared when I got into a relationship, and when he came back into my life, it felt flippant and offhand. We’d exchange elaborate, decorative emails telling exaggerated tales of our daily lives; I’d see him once, and then there’d be nothing for months, sometimes years on end. I knew when he’d read my Facebook messages of course, but he rarely replied.

He agreed to meet me on his birthday so I could take his portrait.

I photographed him in his bedroom, but I never asked him the questions I’d planned to, never got the answers I wanted. I watched the smoke fill the air around him, beautiful and transient, and I cherished our moment together.

Afterwards, I sent him a message asking if we could do it again. We made plans to go on an adventure and I thought I’d photograph him then. I would ask him, when I had him back, all to myself, why he disappeared. But we didn’t go.

In the beginning and the end, Paloma being naked was uncomfortable for both of us. We hadn’t known each other for long when I replied to a message she’d posted, saying I could assist her with a studio shoot. I hadn’t planned to photograph her like this. I snatched a moment at the end of her shoot to ask if I could take her portrait. She agreed, but her confidence seemed to fall away as she shifted from artist to subject. The atmosphere had changed again; I had trouble encouraging her to face the camera. I felt guilty and wondered if photographing her in this way might be some sort of violation. At the end of the day, she deleted the pictures we’d taken for her project off my camera, but left me with mine. I took this a sign that it was OK.

Photographing him feels completely different now. It’s not tender. I don’t feel like I’m recording anything particularly special. He is more confident, slipping between his model poses and looking straight past me. This isn’t the way it was supposed to be.

I’m not hiding how this makes me feel. I can’t believe he doesn’t see it, doesn’t get what this is about, doesn’t understand why I want to photograph him. We’re here, together in this space, and I’m taking pictures of him listening to the music he sent me when we split up. Why isn’t he asking me why?

“Can you play that song you wrote about me when we broke up?” I ask him. “Now the one you sent the day you left.” And off he skips to put it on, waxing lyrical about what a great track it is, or rattling off facts about the artist. Like that’s what I’m interested in.

I am tired. I sit down, but keep on taking pictures. There’s nothing that matters here to capture. He isn’t responding like he did in my head. I hand him my camera, take his cigarette and ask him to photograph me instead.

I smoke while he takes pictures. They’re not what I want them to be.

Going home, I forget to swipe my Oyster card and miss my Tube stop. When Jo comes in, I show her the pictures and tell her what a horrible waste of time today has been. Look through different eyes, she tells me. I do, and I see that every photograph I have here represents something real, even though they’re nothing like I imagined.

I email him and ask him how he found the shoot. I want to understand it from his perspective.

He replies:

“I don’t really know what to say.”

When Imogen arrives Katharine doesn’t seem to know whether or not to let her in. Imogen hasn’t seen her since school (she hardly spoke to her then). Neither of them can relax until Imogen asks her about the dress.

Katharine: The dress is a copy of two of Ginger Rogers’ dresses, because I loved the skirt of the dress that she wore in Roberta, but I didn’t like the straps. So the straps come from another dress she wore in Swing Time that is far more beautiful, but I believe it cost somebody $5,000 to recreate.

Imogen: How much did yours cost?

Katharine: £500

Imogen: Wow. That’s a lot though, isn’t it?

Katharine: Well, £300 to make, £150 for the silk – and it’s pure silk – and £30 for tax! I wanted it because I go to at least one or two balls a year and I wanted a dress that I could literally wear to every single occasion so I would never have to go and buy another one that I didn’t really like.

The dining room is too full to enter. They make their way up to Katharine’s bedroom.

Imogen: Can I move the lamp behind you?

Katharine: You can move anything you like, seeing as it’s headed for the bin.

Imogen: I don’t want everything to fall off this shelf though.

Katharine: I am quite happy to move everything in here, because, as I say, it’s mostly headed for the bin. When the bulb died in this one, I then couldn’t find another one to fit in it. So actually I could just go and buy a new lamp.

There is a silence.

Imogen: You’re much more comfortable in front of the camera than I am.

Katharine: Well, they say you’re either more comfortable in front of the camera or behind it. I’m the sort of person who can take pictures on holiday; of the view, food or alcohol.

Imogen: I’m just trying to think about your pictures on Facebook and what I’ve seen from those...

Katharine: I hardly put anything on Facebook now. It’s weird; I use my Twitter account far more.

Imogen: Oh really? Well I know you were watching TV last night!

Katharine: Yeah, The Apprentice!

Katharine laughs. Imogen trips on something.

Katharine: It’s only an umbrella and a bag.

Imogen: I don’t want to leave here for you to find I’ve broken something!

Katharine: Don’t worry – the bracelet’s on my wrist.

Imogen: What’s the bracelet?

Katharine shakes her wrist.

Imogen: Oh wow. Was that a present?

Katharine: Yeah.

Imogen: From Ian?

Katharine: I saw it in the duty-free brochure and he was like, ‘Erm, I’ll think about it over the weekend’. I was like, ‘They’re having a sale!’ Although I almost died hearing some of the prices. There was this gold sparkly heart that was really nice and I was like, ‘Ah now I know why it’s so nice’ – it was, like, £182. But hey, I’ve got some nice charms.

They head downstairs to the living room.

Katharine: I should just say: when the desk goes, the record player goes.

Imogen: Where is the record player?

Katharine: In that cupboard. It came from my grandmother’s house, so it’s at least been kept. My records are my treasures because I have lots of lovely records. I’ve got some loooovely 1920’s records.

Imogen: Have you?

Katharine: Everyone’s like, ‘You must have paid a small fortune for them’, but do you know what? There’s not a huge following for Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers. I mean some of them will go for enough, just because.

Imogen: I bet.

Katharine: Eventually I can get my own record player out from where it’s hiding under my bed. Along with the printer.

Imogen: Well you’ve just got to sell some stuff and then you can get them down!

Katharine: I’m trying to persuade my parents to buy my sofa.

Imogen: But then won’t you need a new sofa?

Katharine: No, Ian’s got one.

Imogen: Oh, that’s cool. So when’s he moving in?

Katharine: Well, ’cause he’s flat sharing at the moment and his flatmate’s moving out in July. So he’s kind of like, ‘Well I’ll either need to look for a new flatmate or we can move in together’.

Imogen: Is he messy?

Katharine: Well his bedroom wasn’t the tidiest.

Imogen: Sometimes in a couple you have one that’s really tidy and one that’s really messy. Will he move in and tidy or will he move in and just... like it?

Katharine: No, I’ll just find tidying easier. People are like, ‘I’m not coming round to help you tidy your house’. It’s like, ‘No no! You come round and I’ll tidy and you can sit on the sofa and chat!’

Imogen: That’s true. It’s nice to have company.

Katharine: Plus, with the addition of finishing uni, once I graduate, all my stuff can go in the bin.

James was his friend and was living with us when we broke up.

I hated thinking about how he must have thought of me at that time, when I’d resented him for being a constant reminder of what I’d lost. It wasn’t James’ fault of course; he just had the misfortune of being around before it happened and still there after. Eventually, I asked him to move out.

That’s why I was so surprised when I met him on his lunch break and he seemed so relaxed, so friendly. Unprompted, he began to tell me that he understood how hard it must have been for me and, for the first time, I realised how much he cared about me. Somehow, away from the old flat and its fug of hurt feelings, we seemed able to see each other more clearly.

We had a cup of tea in a café opposite his work and I photographed him outside before I left. He fitted right in to the City.

When Rosie began I was spellbound. I’d looked at her pictures, imagined the photographs I might take, but nothing I’d seen online captured this grace and fluidity. I wasn’t sure I could, either.

I’d somehow managed to convince myself that I needed to repair my relationship with her, but now, watching her move, I realised that had just been the lie I’d told myself to get here. I wanted to see her on the pole.

She had made the underwear she was wearing; pole dancing was just a temporary thing, to help her on the way to becoming a lingerie designer. We didn’t talk about it, but I tried to imagine the men leering over her as she performed. I struggled to see her with eyes other than my own. I knew the seediness of strip clubs, the animal urgency, but I couldn’t believe that it would be that way for her. I didn’t view her performance as sexual, but the thought struck me that perhaps, by photographing her like this, I was using her too.

I saw a rat run across the room behind her. We didn’t talk about that either.

It took me two hours to get ready. I went through outfit after outfit, trying to find a way of incorporating the blue shirt he’d bought me not long after we’d met. I was nervous about photographing him – I feared he might judge the way I worked. I tried to forget that Mehdi was a photographer.

We stayed up late drinking red wine and talking, increasingly comfortable with each other. I tried to tell him how much I liked him, but the words stumbled as they came out.

After we’d had sex, we lay beside each other in a dim lit room. I reached for my camera and moved around the bed, photographing him while he unfolded his body in the glowing light.

Look at the picture, the way her slim arm curves around the small of his back, just the way yours used to. Remember the way your hip slipped so neatly under his? Your bodies always seemed to fit together in every position, like infinitely compatible jigsaw pieces. You wonder if theirs feel the same. She’s taller than you; her head doesn’t fit into his chest like yours did – he said he loved that about you, remember?

She is slim and fit, wearing a baby pink dress that, with her blonde hair, makes her look like a Barbie. You hate pink, but you’re envious that she can wear it. Maybe he likes it now, too.

You can’t deny she looks beautiful in this picture; that bump in her nose has become a flat, perfectly formed little flick. Their smiles match. Look at the way the top of her arm protrudes in a sort of slouchy curve – you hate the way your arms do that too, don’t you? Hers are tanned though, well defined. Maybe yours aren’t so bad either? Your gaze wanders to his face; is he really happy? Might this be a façade? They do look so well suited though. You’re not going to argue with that, are you?

You study the picture further. It has 58 likes. You read your way through the comments and ache and ache and ache.

Tom is my neighbour. He was when we were kids, too. I don’t see him often, but sometimes, in our area, we collide.

I knew he was at the allotment that day because of Instagram. I decided to surprise him.

We went for a walk, shared a smoke, sat on a bench. I photographed him there. He’s a painter. The splatters of bird poo were like brush marks, we agreed.

I didn’t see her as much as I’d wanted when she was pregnant: she’d moved away; things seemed so different. I photographed her on three occasions; we both knew it was the only time we were likely to spend together for a long while.

She was abuzz, bobbing from excitement to tearful anxiety at the prospect of the unknown. She’d fall asleep between shots, waking up to pose like a statue, but before long she’d become uncomfortable and get lost in her own conversation with the baby that was to come.

I told her that her pubic hair was exposed. She said it was only natural: it didn’t matter. When she noticed the stain on her pants she asked me if I could Photoshop it out.

Helen is one of Imogen’s best friends; she’s always the first to tell Imogen she’s her biggest fan whenever she posts a picture online. Imogen tries to keep tabs on what she’s up to. They barely see each other.

While Imogen photographs her – because she is photographing her – Helen tells Imogen about her life now. She is studying midwifery. She puts on her new uniform for Imogen and tells her what she

has learned.

Imogen: OK – we’re recording. What were you saying about your thing?

Helen: (Points at a piece of paper) What do you think any of this means?

Imogen: I don't know?

Helen & Imogen: “Spontaneous vaginal deliveries witnessed.”

Helen: SVB means spontaneous vaginal birth. G3P1 +1 means gravida three – she’s had three pregnancies. Para means how many live children she’s had. So she’s had one live child plus one either miscarriage or abortion. So that’s what that means. And then it tells you about the details of her birth and how the third stage of labour was managed. Do you know what the third stage of labour is?

Imogen: Giving birth?

Helen: No. It’s when the placenta comes out after the birth. And I’ve written how they’ve given birth. The position they were in.

Imogen: When I watch One Born Every Minute I always have to hold my breath when the baby’s born until I hear it cry!

Helen: It’s not just about if they cry. It’s about if their heart is beating and what their colour is like. It’s quite normal for it to take a few minutes. I’ve seen one that needed some help, but I haven’t seen any that needed a lot of help yet. I’m sure I will. I haven’t seen a stillbirth yet.

Imogen fires the shutter.

Imogen: Do you know quite quickly if something goes wrong? And you still have to carry on...

Helen: What do you mean?

Imogen: If the baby dies during labour.

Helen: I haven’t been in that situation yet, so I don’t know... If it’s a confirmed stillbirth they would probably induce normal labour.

Imogen: That’s awful. So you have to go through an entire painful labour?

Helen: Yeah. That’s what my mum had to do.

Imogen: Really? I had no idea.

Helen: Back then, they didn’t show you the baby or anything. They’d just take it away straight away. Whereas today you get asked if you’d like to spend time with the baby and encouraged to have bereavement counselling. She didn’t really see it at all.

Imogen: That’s awful. Do you speak to her about it?

Helen: Yeah, I speak to them about it. I remember when I was younger, asking my dad. I don’t think I knew about it, but I asked him ‘What is the saddest thing that’s ever happened in your life?’ And he said ‘When your mum lost a baby.” I think that’s when I first knew about it. You think your parents are so strong, but it made me realise how awful it must have been to expect a baby and for it not to come. But yeah, my mum does talk about it. I think it’s because she’s a bereavement counsellor.

Imogen: Oh really? I didn’t realise that she’s a bereavement councellor too.

Helen: Well she’s a normal counsellor, but she specialises in bereavement as well.

Imogen: I wonder if that’s why your mum went into it.

I wonder if it’s why you’ve gone into midwifery?

Helen: Yeah, maybe. I have always loved bumps! Especially when my sisters were pregnant.

Imogen: I wonder if that’s why your mum went into it. I wonder if it’s why you’ve gone into midwifery?

Helen: Yeah, maybe. I have always loved bumps! Especially when my sisters were pregnant.

Imogen: I’m not sure I’ve ever felt a baby kick, you know. Actually that might not be true. I’m really hungry.

Helen: Would you like some strawberries?

Imogen: Yes, please, although I should probably go, you know.

I should probably catch the train earlier rather than later.

We had only met the once, when he messaged me to ask if I’d play the role of his lover in a short film. Ruaidhri intrigues me, and I find myself using photography as an excuse to spend more time with him.

One afternoon I ask him if we can recreate a picture of his grandfather that I’ve come across on his Facebook page. That is something he’s always wanted to do, he says.

His grandpa was a handsome man, sat at a kitchen table in Italy in the late 1950s, with light streaming through the plants and onto his breakfast. He hadn’t been permitted to share a bedroom with Ruaidhri’s grandmother at the time. Ruaidhri enjoys the innocent romance of it all.

People commented on the picture, remarked on the resemblance between the two of them.

I see his bedroom for the first time that day. It’s beautifully arranged, almost set-designed, with French novels, oil burners and tin soap dishes dotted around – a careful, curated style I recognise from his blog. I can’t photograph them, he tells me; that is something he wants to do himself. For a moment, we are two artists with hidden, conflicting agendas. I wonder what he wants. If I am not allowed to take photographs of his trinkets, then why am I allowed to turn him into his grandfather?

A few plants and a fortunate shower of sunlight transform his living room, and the shoot begins. But Ruaidhri is tired, hungover, and I am taking too long perfecting the shot. I know when it is my time to leave. I had hoped to be with him longer.

For our second meeting, I’ve asked Ruaidhri to photograph me, but when the day comes I try to postpone it. He tells me he won’t let me put my work on hold any further and that he has prepared some questions he’d like to ask me.

I set up a camera to record us and sit there, tense and unready. He opens a box of panettone, places it on the table, and invites me to eat. He has prepared a playlist for the day. He puts it on and asks his first question:

"What is your project about?"

I am thrown into panic. I don’t know anymore.

Ruaidhri jumps up and escorts me from the room – my room– to the top of the basement steps, where he photographs me.

I wanted to photograph him too, but my camera is in the next room, recording emptiness. I’ve planned for some sort of conceptual cold war, and he’s disarmed me with a playlist and a panettone.

“Describe your favourite photo from memory."

At this moment, I don’t have one. Nothing and no one comes to mind. I tell him I can’t answer questions like this under pressure.He drags me into another room to ‘think’ about my answer and takes more photographs.

In my conservatory, I light a cigarette.

In the end, I describe a picture of my mum that my dad took in the 70s. I don’t think Ruaidhri’s especially interested in that; I think he’s interested in the fact he’s put me on edge.

I smoke while he takes pictures. I think of one of the women I saw in a picture on his blog – a 60s model smoking – an image I knew he liked. I pout my lips and exhale through a heavy fringe. I don’t want to disappoint him.

The third time, I ask Ruaidhri if he will let me take his portrait during one of his own film shoots. He introduces me to the cameraman via email.

We will also be joined by my friend Imogen who will be taking some production photos. She may well shoot some additional wides of the three of us.

It is very quiet when I get there – focused and disconcerting. Ruaidhri has two cameramen working for him. I already know one of them, but my arrival doesn’t seem to trigger much of a response. Benignly ignored,

I get out my camera and take silent photographs of them filming a still life.

It isn’t until halfway through the day, when I have relaxed into things, that I realise that the sounds of our voices, my camera shutter and our movements are being recorded. It suddenly strikes me that my presence plays a part in Ruaidhri’s work as much as his does in mine. I wonder whose project it is today.

I soon find myself taking production shots and forget why it is I am here.

Miss had sent a student to fetch me from reception. I was convinced she planned on embarrassing me somehow, on throwing me into a sea of teenage faces, watching me drown. As I entered the classroom, she waved, tossed over a smile and carried on teaching. I sat on a chair, faced the class and learned about the amount of protein in cheese.

When the break bell rang and I started taking pictures, she asked

her students to join her but they ran away from my camera. She was sad about that – I thought perhaps they acted as some sort of collective comfort blanket. She would help define the people they would become – in return do they define who she is now? That dreaming sea of faces that rolls in and out every year, different but the same?

Before I left, she introduced me to the next class. I felt important, not embarrassed. She hugged me. It was a nice hug, and I felt sorry to say goodbye. I hadn’t the last time.

While I spent the afternoon photographing Helen, Basil was working in the garage at the back of the house. I popped outside to see him and took his portrait while Helen made us some tea. I asked him about motorbike parts.

When Helen joined us, she didn’t seem to understand much of it either. We weren’t out there very long.

Christina is a yoga teacher. I’d see her on Tuesdays, in class. She posts pictures of herself stretching online. I was always blown away when

I looked at them – she’s astonishingly flexible. She told me that, when she was a child, she trained to be an Olympic gymnast. Her mother stopped her – the training was too much, apparently, but it obviously stayed with her.

I’d been to Christina’s house once before I photographed her, with friends for dinner, but never into her bedroom. She told me she never usually presents herself in such explicit positions online. She was worried about being too provocative, I think.

Before we met in person, he called me ‘sister’. We do have a connection: he is an activist and the main subject of a documentary my brother made about the killings of people with albinism in Tanzania.

When I meet him for the first time in Amsterdam, I am already overwhelmed. Josephat is used to having his picture taken by now, although he doesn’t seem to understand why I want to take it. He’s partially blind, and I don’t know if he can see me when I ask him to look at me. I only take a few shots.

He tells me I must use my photography to make great change in the world. I think about it.

I can’t stop thinking about it.

Bea had become a dancer; I hadn’t. Hearing her voice again threw me. It was familiar and different, like déjà vu. She’d retired from performing, she told me, but said that she’d still like to put on her leotard and show me some poses.

She stretched in her hallway, complaining about old injuries. You miss this, I thought.

At one point, she fixed her eyes on me through the lens, asking me, theatrically, ‘What’s my story?’

I said:

‘Your dog’s just been run over.’

She looked at me harder.

I wonder where Joe goes. He seems such an intermittent part of

my life: brief, intense flurries of connection, and the rest is silence. He disappeared when I got into a relationship, and when he came back into my life, it felt flippant and offhand. We’d exchange elaborate, decorative emails telling exaggerated tales of our daily lives; I’d see him once, and then there’d be nothing for months, sometimes years on end. I knew when he’d read my Facebook messages of course, but he rarely replied.

He agreed to meet me on his birthday so I could take his portrait.

I photographed him in his bedroom, but I never asked him the questions I’d planned to, never got the answers I wanted. I watched the smoke fill the air around him, beautiful and transient, and I cherished our moment together.

Afterwards, I sent him a message asking if we could do it again. We made plans to go on an adventure and I thought I’d photograph him then. I would ask him, when I had him back, all to myself, why he disappeared. But we didn’t go.

In the beginning and the end, Paloma being naked was uncomfortable for both of us. We hadn’t known each other for long when I replied to a message she’d posted, saying I could assist her with a studio shoot. I hadn’t planned to photograph her like this. I snatched a moment at the end of her shoot to ask if I could take her portrait. She agreed, but her confidence seemed to fall away as she shifted from artist to subject. The atmosphere had changed again; I had trouble encouraging her to face the camera. I felt guilty and wondered if photographing her in this way might be some sort of violation. At the end of the day, she deleted the pictures we’d taken for her project off my camera, but left me with mine. I took this a sign that it was OK.

Photographing him feels completely different now. It’s not tender. I don’t feel like I’m recording anything particularly special. He is more confident, slipping between his model poses and looking straight past me. This isn’t the way it was supposed to be.

I’m not hiding how this makes me feel. I can’t believe he doesn’t see it, doesn’t get what this is about, doesn’t understand why I want to photograph him. We’re here, together in this space, and I’m taking pictures of him listening to the music he sent me when we split up. Why isn’t he asking me why?

“Can you play that song you wrote about me when we broke up?” I ask him. “Now the one you sent the day you left.” And off he skips to put it on, waxing lyrical about what a great track it is, or rattling off facts about the artist. Like that’s what I’m interested in.

I am tired. I sit down, but keep on taking pictures. There’s nothing that matters here to capture. He isn’t responding like he did in my head. I hand him my camera, take his cigarette and ask him to photograph me instead.

I smoke while he takes pictures. They’re not what I want them to be.

Going home, I forget to swipe my Oyster card and miss my Tube stop. When Jo comes in, I show her the pictures and tell her what a horrible waste of time today has been. Look through different eyes, she tells me. I do, and I see that every photograph I have here represents something real, even though they’re nothing like I imagined.

I email him and ask him how he found the shoot. I want to understand it from his perspective.

He replies:

“I don’t really know what to say.”